I didn’t want to go to Hutchmoot.

When my wife told me that she’d bought me tickets because, wise as she is, she knew I wouldn’t do it on my own, I immediately thought:

“Oh crap. Now I have to go.”

For those of you who may not know, Hutchmoot is the annual gathering of the community of (and surrounding) the Rabbit Room. It’s a weekend celebrating story, song, food, art, community, and Jesus. Sounds kind of wonderful, right? And I knew this before I went to it, because of how vocal the whole Rabbit Room Chinwag Facebook group was about it.

But even though I knew all this, I had a lot of reasons for why it wasn’t a good idea for me to go, ranging from the very real “Linnea will be three weeks out from her due date,” to the also very real social anxiety, to thinking that I didn’t belong with such an accomplished, artistic group of people. I am an introvert, and I hate crowds. I might have been just a little nervous that all of these enthusiastic people I’d met on a Facebook group were actually a super-secret cult that performed sacrifices of Hutchnewbs on an altar of Tolkien novels to Andrew Peterson.

Thankfully, my wife’s good sense (and years of training in snagging Door County campsites) paid off, and she convinced me to drive the eight hours to Nashville and attend.

That first night was crazy. I was tired from the drive and experiencing Hutchgaze, in which you stare creepily at a person trying to determine if they look like their profile picture before greeting them sheepishly by both first and last names. But I was in line for only a few moments before I got a big hug from Bailey Berry McGee and the greeting that would become the mantra of the weekend: “We’re so glad you’re here!”

I could go on and on about the highlights: John Cal’s songs and stories that made me look at the simple act of eating together in a whole new light, the craftsmanship in every creative work, the free-flowing Ethiopian Guji, the Poetry Pub championing each other and the oft-overlooked poetic value of cheese, the total welcome of every face, a list a mile long of things I can’t wait to read and listen to, and the session notes that I will continue to pore over.

(I wasn’t planning to gush. I was going to hold it together a little better. But as I think back over the weekend, gushing seems to be in order.)

Let me narrow it down a little, for all of our sakes…

When I first came in, I was cycling through anxiety, envy, and discouragement. I was coming out of a dry creative season. I had experienced some pretty deep disappointment recently and was muscling my way through it the best I could. In general, I was exhausted and wondering if this writing thing was even worth all of the effort.

What struck me most about Hutchmoot was that so many of my fellow attendees (at least the ones that God opened up conversations with this year) seemed to be in similar spots, or a little down the road in either direction from where I was. Many have dreams of doing more creative work and maybe even getting paid for it someday, and many are feeling like that might never happen. Many are in the thick of some grief, loss, or discouragement. Many are grappling with what to do next, or how to best steward the creative passion within them. We all are people who need a hug, a song, a snack, and the assurance that we aren’t striving alone or in vain. And we’re also all people who are willing to freely give those things to each other.

Maybe it’s an artistic personality thing, or maybe it’s just the nature of the landscape when it comes to creative work — but the sense of companionship and commiseration was truly a balm to my soul. It was remarkable just to sit across the table from someone I’d met yesterday and think: “you too?” It was something I didn’t realize I needed as much as I did, to know that I’m truly not crazy, nor alone.

And if you’re a creative who is struggling right now, you don’t need to go to Hutchmoot to know this. You’re not crazy. You’re not alone.

Of course, we all went back to our homes and communities bearing within us this knowledge, a kind of ember to keep us warm on the way. Hutchmoot, for all of its wonderful immediate welcome, is not a place to make a home. As Andrew Peterson said on the first night: it’s a wayside inn. It’s Rivendell, a homely place – but not the final Home, or even the earthly home I am called to inhabit. It’s a place where I caught a vision for homely-place-making in my own community, so that as I drove those eight long hours back to Middlebury, IN my mind was blazing with ideas.

It was as if Hutchmoot held up a mirror in which I could see myself more clearly: a beloved, broken child of God who likes to create stuff. And then it gave me a swift kick in the ass and said, “Now that you remember who you are and Whose you are, go do what He tells you to do where you are. Here are some tools you can use, and some people who will walk alongside you.”

And thankfully, those people didn’t sacrifice me to Andrew Peterson.

Speaking of creative community…

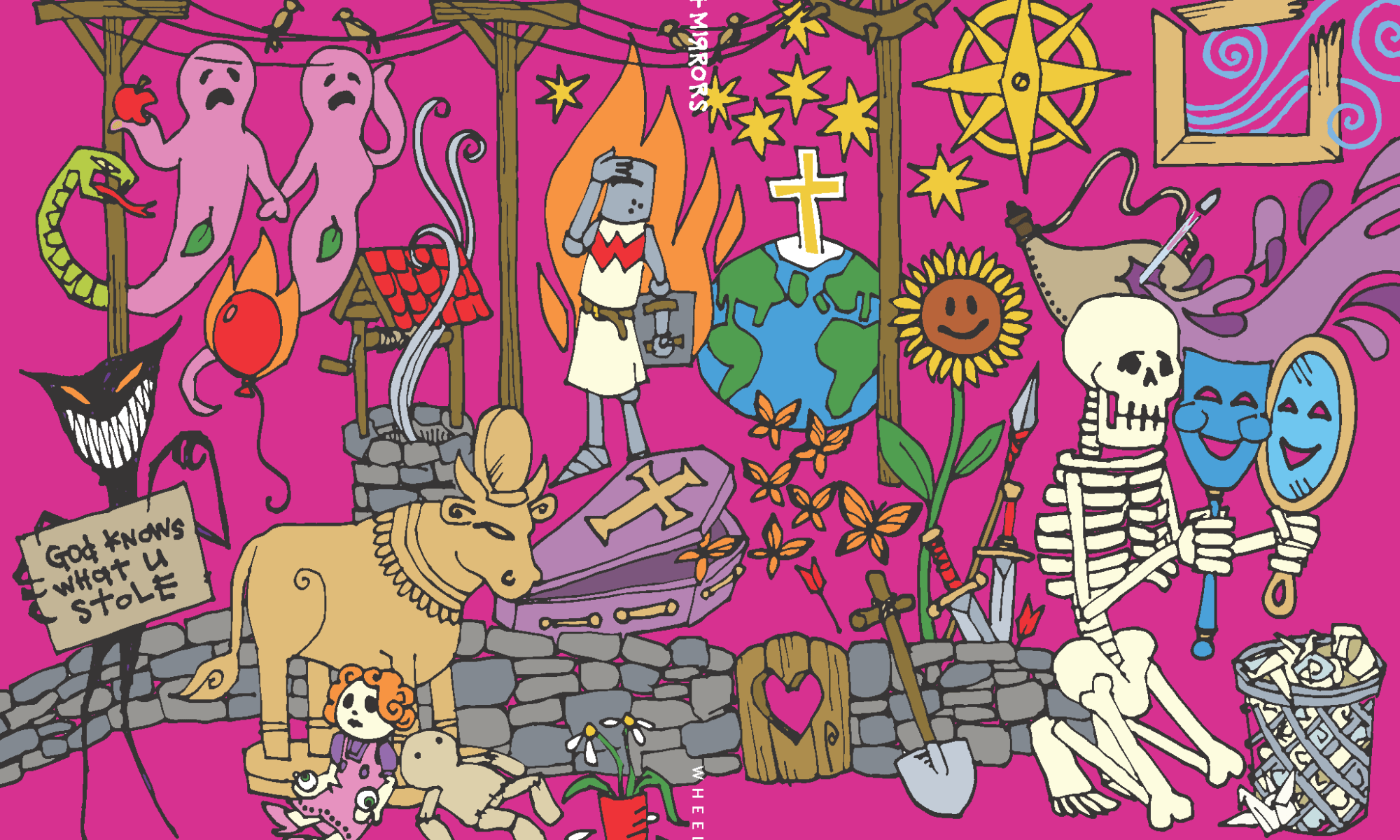

I’ve been running a campaign on Indiegogo to create a new hardback poetry book with original art. With the help of dozens of friends and family, we’ve reached 85% of our funding, with only seven days to go! If that sounds interesting to you, we’d love your help to boost us over the top! Go here for more info, and thanks for considering!!