My wife is taking pictures again, and the golden hour is upon us – in more ways than one, because at the height of summer it occurs immediately after the kids’ bedtime. She is roaming the acreage of my childhood home, kid-free, capturing north-central Indiana with its meadows and sloping forests. The sky is a ripe nectarine, fuzzy orange fading to lavender, and the sun sinks his teeth into it, splattering juice in slow motion.

My mom comes in from the garden, where she has been harvesting early tomatoes and tomato hornworms at the same time. She scrutinizes the former and grimaces at the latter. We set aside one chubby hornworm to show the kids tomorrow; the rest are damned to the smooshy place for their sins against tomato-kind. My wife sets her aperture and snaps shot after shot – Mom carrying the bushel basket, greens and reds, close-ups of marching caterpillars.

Linnea is scrolling through her evening memories on the wide grey porch, swaying on the swing, and I’m tapping away at my keyboard when the epiphany occurs.

Blinking lazily, the first firefly of the night makes its regal ascent from dirt to sky. As I watch it rise and fall, I am aware of others in the periphery of my vision. They rise like mist from the fields until the evening is scattered with their phosphorescence.

As if responding to an inner call that only the recently put-to-bed can hear, our three eldest children suddenly appear at the screen door, harmonizing oohs and ahhs.

“Fireflies!”

They’re out the door before you can say “goodnight,” belatedly yelling back to us porch-dwellers, “Can we catch some?” They are skipping barefoot in the grass, disrupting flight patterns. My wife and I glance at each other. The prospect of tired-out kids sleeping soundly until morning is within our grasp. We wordlessly agree to let them romp a little longer. Summer will not last forever.

Nadia and Kai have caught fireflies before, both to keep as glowing night lights on their bedside table, and for the sheer joy of catching something and letting it go free, no strings attached. They have learned to cup their hands to avoid snuffing out any unfortunate soul by this time, although Kai still periodically appears before me, triumphant, with glowing smears on his hands. For Percy, however, this is the first time he’s really been able to participate, and he is so excited he can’t stop shouting.

He clumsily snares one and exults, “I caught one, Daddy!” before it narrowly escapes its doom and zooms into the sky. The ones he catches seem to fly away faster than others. He is unperturbed and trots away after another. Nadia, coltish at six, runs up then. She may have more years of experience with fireflies, but that doesn’t quench her joy in them.

“Mommy, mommy, mommy! I just saw a firefly…” she pauses for dramatic effect and widens her eyes, “…land on my dress!” This is the child’s prerogative: to be utterly blessed by six little legs clinging to a nightgown. I tend to brush these things aside, adult as I am, with my diminishing capacity to perceive and appreciate true blessings. Maybe I should look closer at the mysteries of crawling things. Or maybe I’ll let my kids keep reminding me of them.

The whole planet is glowing now with the different magic of early evening. The sun is nestling under the covers, leaving only a few streaks of magenta staining his pillow. The march of the fireflies starts to mirror the procession of the stars, appearing one by one. When I focus on one the others wink at me.

A recently-sung (and apparently ineffectual) lullaby plays in my head.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star. How I wonder what you are…

My wife adjusts shutter speed for low light and the camera clicks in slow motion.

Maybe it’s because I’m hopelessly nostalgic on the best of days, but in that snapshot moment, I’m transfixed by it all. Here are my children, chasing insects through the same field I chased insects through twenty years ago, against the same sunset, in front of the same house. The world is repeating itself before my eyes, and I want to record it so I can play it over and over again. I don’t think for a moment I’m alone in this as a parent. We all want to bend time to our wills. How does a single second hold so much weight?

Perhaps a solitary grain of sand in the hour glass is also infinite. After all, a day and a thousand years are the same to the One who set them in motion. If He takes such care to pack them both full to bursting with purpose and meaning, shouldn’t we weigh them out well? They flit away from us like fireflies, but their fleeting nature only serves to capture us further.

My children are spinning wheels of gold against the darkening green of the lawn, their bare feet shimmering as they traverse the back of the earth in pursuit. I wonder sometimes if angels laugh at us, these inane little creatures that run around catching even tinier creatures just to let them go again. Why are they so entrancing to us, these little glowing things? Why do we love to catch them and study them? Where does that light come from? Look closer, maybe we’ll find out. But if we somehow did, maybe we wouldn’t enjoy catching them so much.

I beckon to Nadia to come and see the tomato hornworm we caught. She clambers up the porch steps and peers over the edge of the terrarium. “What is it?” This is a tomato hornworm. He eats tomato plants, and soon he will make a big fuzzy cocoon, and then he’ll turn into a giant fuzzy moth. She turns inquisitive eyes to me. “How does he turn into a moth?”

It’s like dissolving from the inside out, having all your cells rearranged, and coming out of it alive and with wings. If you cut open cocoons to see what’s inside before they’re moths, you’ll just find goop. Somehow that goop (tellingly made up of imaginal cells) becomes an adult moth within a short period of time. I tell her this in less words.

Her eyes widen. “Wow!” And she flits over to tell Mommy this new secret. Mommy responds with satisfactory amazement. Nadia giggles a little at the response and nods knowingly, then flutters back to the fields to chase more fireflies.

Knowing things seems to be much less compelling than enjoying them.

Up above the world so high, like a diamond in the sky.

The moments, the lights, the stars, my kids, everything is constantly shifting, and the breakneck speed of parenthood allows for little relaxation and less contemplation. When I’m rooted to the porch swing, when I’m stunned into silence, when the world creaks on its axis and the universe winks in my periphery, everything becomes precious and I want to cradle it and never let go.

There are names for this feeling based on which direction you look down the timeline — “nostalgia” for the past, “wonder” for the present. In future tense, Lewis called it sehnsucht, a deep longing for a place we’ve never been to. I see glimpses of it here, everywhere, because this world is only a shadow of things to come. It is mystery and wonder and familiarity all wrapped into one, and it always slips away from us all to quickly, like the golden hour. But it’s here right now, for a moment, as I watch the day fade around my children, who are chasing down illumination in the fields.

I know many who think of this sort of feeling as sentimentality, who believe that it is useless when it comes to keeping up with the incessant demands of the daily grind. How does this wonder fend off the brutality and hatred teeming in every corner of the world, or stop a bullet, or tear down a wall, or advance a kingdom? It would be easy, and it has been, for me to be embarrassed by my love for fireflies and sunsets. What light can a single firefly actually give? What good do any of these beauties and longings offer in a world gone to hell?

Much good, for the faithfulness of God frames each snapshot, the humor of God winks back at us, the mystery of God wriggles out of our fingers yet again, the love of God paints the sky for nothing more than sheer enjoyment of its beauty. We write and paint and sing and dance because we can’t get enough of God. And we long for the day when there will be nothing between us and Him.

Nights like these align our hearts to wonder at Him again, when circumstances and self fall away and the naked surprise is revealed. We see again, through His creation and care for us, that God is involved and present and working for our good and His glory. These nights repeat what my soul needs to hear over and over: “Behold, I am making all things new.” And we sit on the periphery and let the longing to be made new ache within us and our children, and we come away ready to fight again another day.

So my wife and I watch the fireflies and stars and children rising and falling on the breeze for several more minutes. Then we get that familiar twinge of parental responsibility and call to them across the lawn, “Time for bed!” We eventually succeed in tearing them away from it all with the promise of breakfast and more wonder in the morning. Nadia knows the drill by now and is content with the opportunity to stay up later than normal, and Kai is happily thinking about cereal now. My wife, camera dangling in a loose grasp now that the memory is safe, ushers them through the screen door and lingers, languid in the dimming light, watching our younger son. Percy is still utterly transfixed by the fireflies.

“Can I catch one more, Daddy?”

Twinkle, twinkle, little star…

“Just one more, buddy.”

He reaches out to one, chubby toes glinting in the sea-green undergrowth, and his face lights up. He cups his hands, as we’ve taught him, and gently captures the last firefly of the night. He runs to me to show me his catch, and just as he arrives it slips out. It’s been pressed down, shaken together, and now it’s running over his fingers, slipping away into the twilight with a final glimmer.

He looks at us and squeals with laughter, enthralled once more because it escaped him, as all mysteries must.

How I wonder what you are.

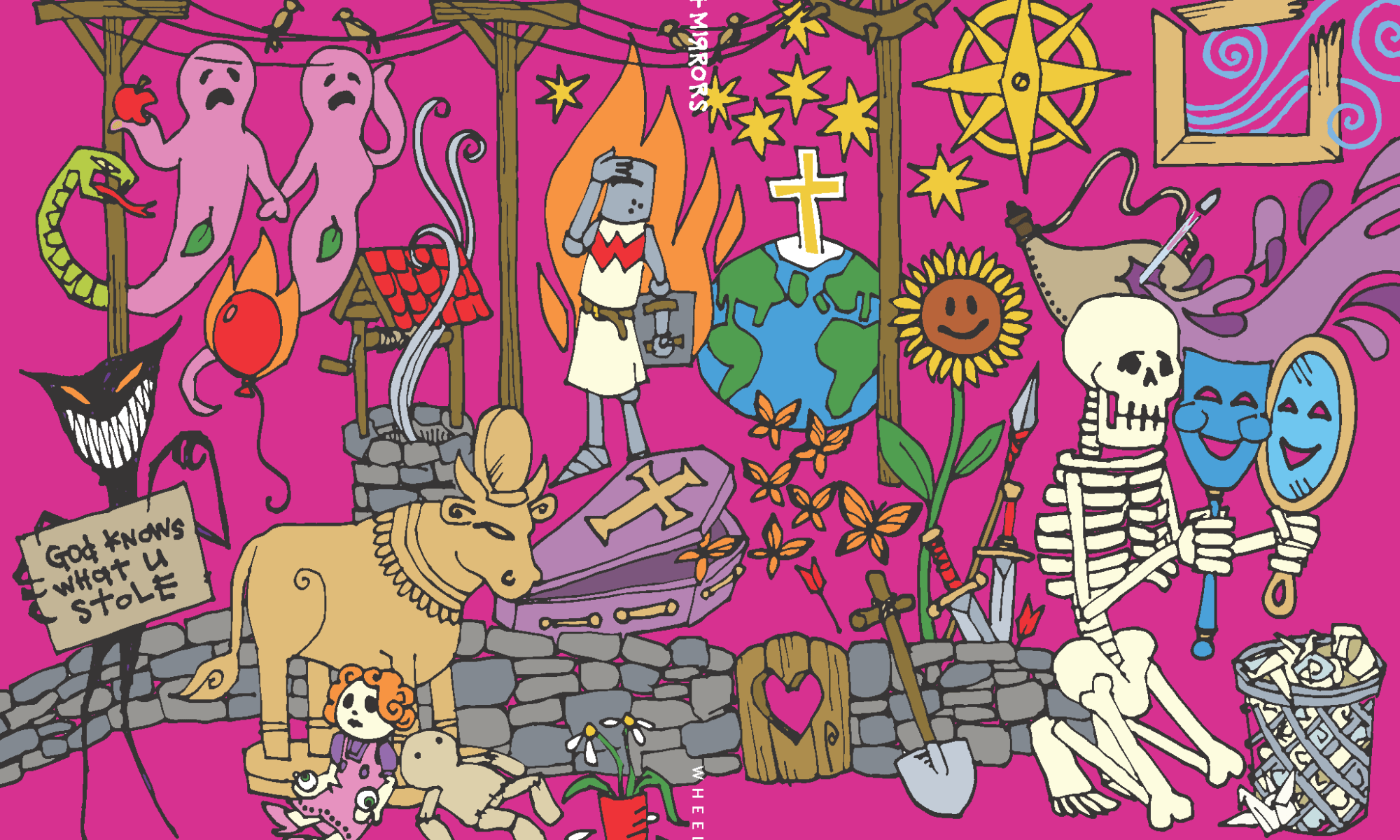

(photography by Linnea Wheeler)